Humpback whales are my gateway drug. The first whale I ever saw in person was a Humpback whale – in 1987 off the coast of Province Town, MA. Then came Star Trek Four – the Search for Spock aka the one with the whales. That was followed by an eye to eye experience while in the waters off of Maui. I’ve been hooked ever since, so I thought the best way to celebrate Humpbacks is to learn and share all about them.

Humpback whales, known scientifically as Megaptera novaeangliae or Great wing of New England, are not the largest of the whales, that title goes to the Blues who are both the current and all time champions of size for mammals on earth. What they might best be know for is their curiosity. They seem to want to know what were doing in our boats out on their water, they’ve been known to ‘rescue’ humans from sharks, and get between Orca and other marine mammals. They also sing songs lasting up to 30 minutes, change year after year, and are shared among Humpback whale populations. That song is part of what made them the poster kids for the Save the Whale movement and helped bring most industrial whale hunting to an end.

Adult Humpbacks average 50 feet and 45 tonnes in weight, making them the sixth largest of the great whales. Their skin is generally dark gray to black on top, so from the surface they look like a shadow, or a log floating in the water. They’re not easy to see at a distance, with one exception – their blow spout. As a Humpback comes to the surface they let out a burst of air, up to fifteen feet high, through their blowhole. The blowhole is on the top of the whales head, near the front, and is to whales what nostrils are to land mammals. Also, if you’re close enough, you’ll get a whiff of sea and fish. It’s an acquired smell, trust me.

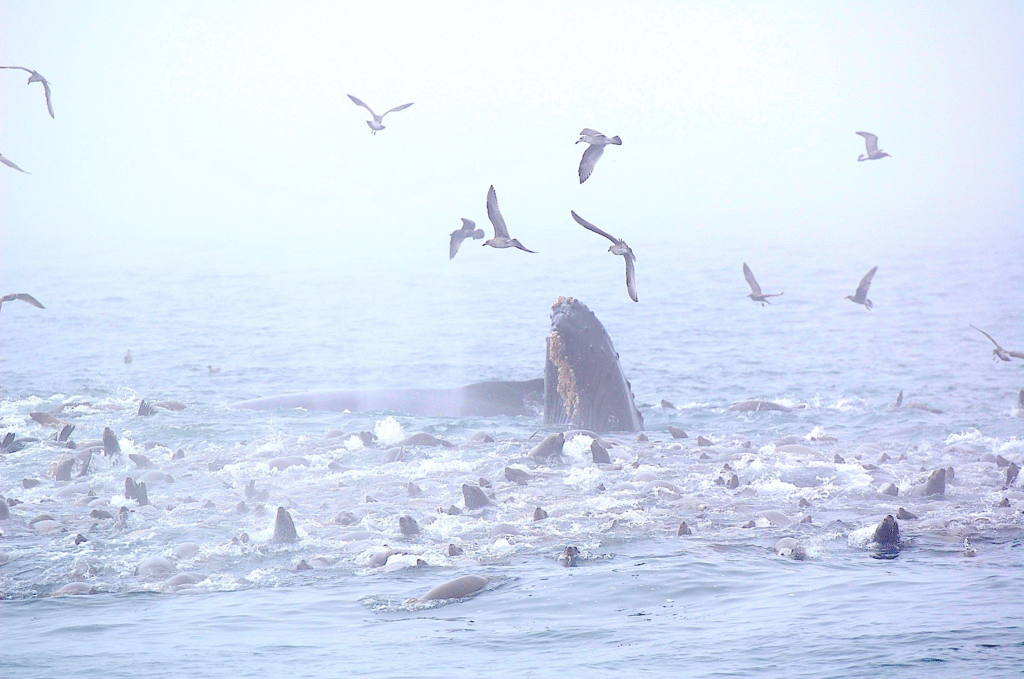

The two photos show some of the bumps Humpbacks have around their chin and along the top of the their head. These are call tubercles and each one has a hair at its center, which is part of why they are classified as mammals. Why do they have the bumps and why is there a hair there? We don’t really know, but the bumpy nature of their heads adds to their distinctiveness.

After a blow, the next sign you’re looking for is the shape of the whale’s dorsal fin. The dorsal fin rises from the back or “top” of the whale. It can be anything from nearly non-existent in Belugas, to 6 feet tall, and solid black in Orcas. For Humpbacks, the dorsal fin is small, triangular in shape, and sits atop the distinctive hump that gives them their common name.

If you’re lucky enough to meet a Humpback that likes to very close, hang around and explore boats, sometimes referred to as “mugging”, then you’re in for a treat. Sometimes Humpbacks will rise straight up out of the water until its eye is near or above the waterline in a behavior called a Spy Hop. Like other whales, Humpbacks can see both above and below the water, so they really are looking at us and our metal machine.

While the whale is raising its head out of the water, you’ll often be able to see the underside of its chin, which can be any color or mix of colors from dark gray to white. Humpbacks acquire collections of barnacles, which can build up under its chin.

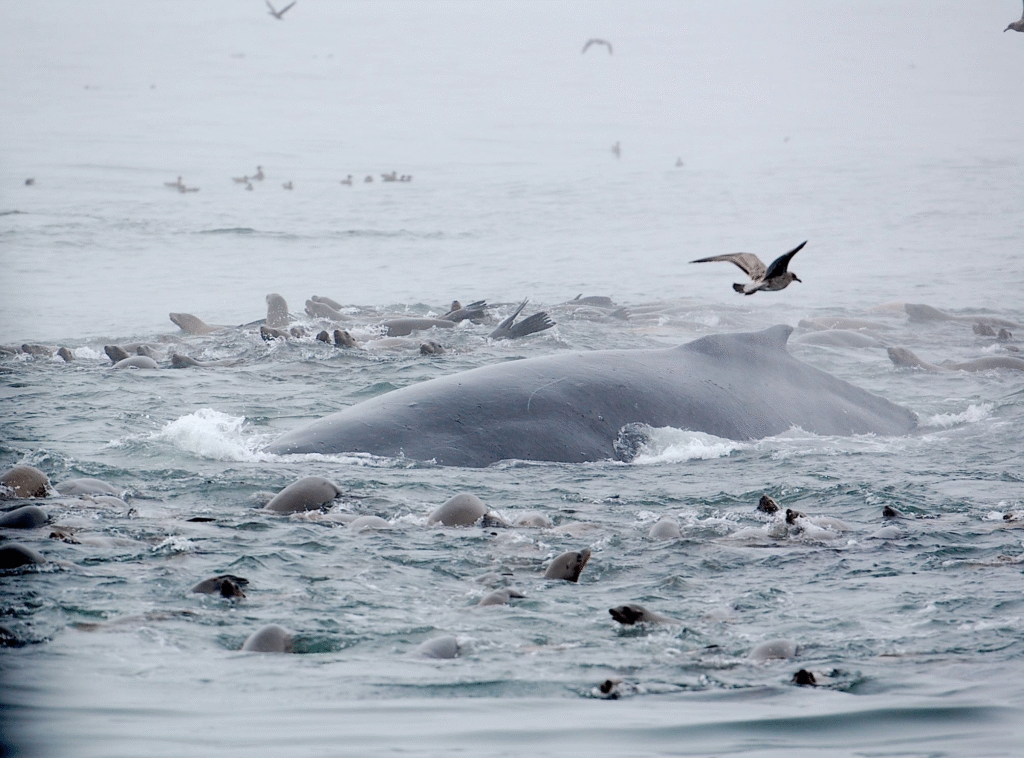

Humpbacks are filter feeders, meaning they strain their food from the water. Instead of teeth, they have plates of keratin fibers that hang from their upper jaw, like rows of bristle brushes, which they used to trap and filter out the fish they want from the water around them. These plates are called baleen and are what distinguishes some cetaceans from their toothed cousins.

To facilitate their large meals, Humpbacks, and some other large whales, have lines, or pleats, called rorquals, which start near the chin and run down toward their abdomens. As the whale fills their mouth with gallons of fish and water, the pleats spread wide to give them room to hold the volume of water they’ve gulped. Then, as the whale pushes the water out, trapping the fish inside their mouths, the rorquals fold back down against the whale’s body.

Another amazing behavior is a breach – when a whale hurls itself, either partially, or on rare occasions, entirely, out of the water. There are a lot of theories about why they do this. Some beehive it is a form of communication, since sound of their impact travels a long way through water, others suggest it part of courtship displays or battles for dominance during mating season. And sometimes its a youngster learning and having fun.

You can watch an fantastic video of two Humpbacks breaching here

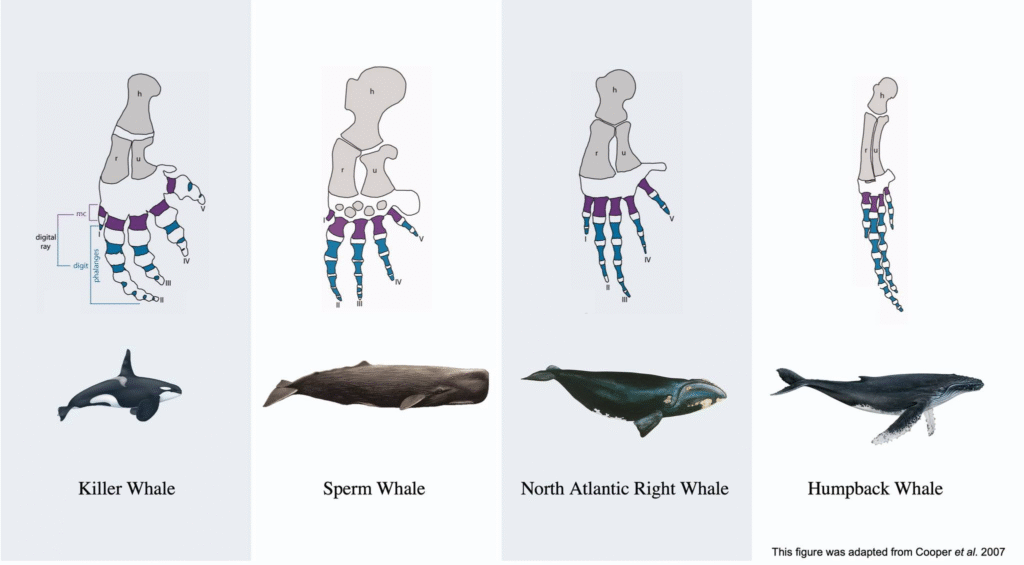

One of the most distinctive things about Humpbacks whales are their pectoral fins. In a Humpback the pectoral fins average fifteen feet, or one third of its body length. These long limbs are usually white with patches of gray, again, color varies from group to group. Pectoral fins are the “arms” of a whale, the bones having adapted over millennia for use in water instead. The trailing edge of a Humpback’s pectoral fin has a row of tubercles which allow the whale a great deal of control as they turn and move through the water. The fins’ size and weight also makes them powerful weapons, along with its large tail, when fighting off predators.

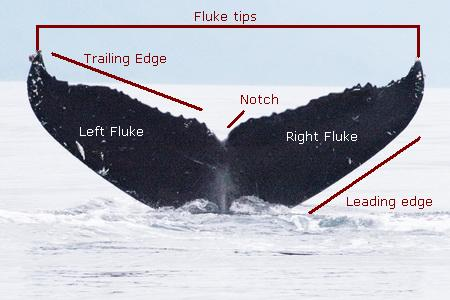

The Humpback’s tail fluke has a few distinctive features as well. The top, or dorsal, side is mostly dark gray a notch at the center divide between the right and left fluke. The trailing edges will have a variety of markings, some of which will last through the whales life, while others will change, and new ones appear as the whale grows, encounters fishing gear, or predators who leave teeth marks, and circular barnacle scars. The pigmentation and markings on the under side of the tail fluke are distinctive enough to serve as Identification marks for individual whales. After 50 years of collecting photos, we now have multiple catalogs of ID photos for various Humpback populations around the world. There are a growing number of catalogues for other whales as well. As the technology to process and match the millions of photos being taken and uploaded has increased,so has our understanding of where and when these whales travel and even who they travel with year after year.

And last, bur not least: one of the things Humpbacks are best known for: the fact that they sing.

Humpbacks communicate using different kinds of sounds for different purposes. Their songs are communication but they are also are much more distinctive and complex in form and, most likely, in purpose. The songs contain distinct phrases and sequences that repeat in specific sequences for up to 30 minutes at a time. Additionally the songs evolve from year to year and spread across populations with the changes appearing to flow from west to east through the oceans. You can listen to a 2018 recording of Humpbacks singing in Monterey Bay here. We also know that only males sing. And, until recently, it was believed that the songs were only sung in the breeding areas. We now have recordings that show at least some humpbacks also sing in the winter feeding grounds of Monterey Bay. There is a lot to unpack about Humpback whale songs, so I’ll do an entire issue about this topic down the line.

Conservation and on going threats

Humpbacks, along with most whales were hunted to near extinction by commercial/industrial fishing in the 18th and 19th centuries . Even after the establishment of the International Whaling Commission, who’s work was focused on managing the stocks of whales so they could be sustainably hunted, whales continued to be hunted. This (mostly) changed in 1972 when Richard Nixon signed the Marine Mammal Protection Act which “prohibits the “taking” of marine mammals, and enacts a moratorium on the import, export, and sale of any marine mammal, along with any marine mammal part or product within the United States. The Act defines “take” as “the act of hunting, killing, capture, and/or harassment of any marine mammal; or, the attempt at such.” In 1978 New Zealand enacted their own MMPA.

The success of marine mammal conservation and protection projects has allowed many whales to rebound. In 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) took more than half the Humpback whale populations off the US List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Estimates now put the worldwide Humpback whale population at around 200,000 individuals.

Eco-tourism has brought more people into contact with Humpbacks, generating more photographs which in turn brings us more information about their lives and their migratory paths. Advancements in technology have allowed us to hear them singing night and day, with less harm to the whales, while generating more information for us to study. While most Humpbacks are no longer at risk of commercial hunting they, like the other whales, still face multiple human connected dangers.

- Ship strikes happen when a whale and a boat collide, often within shipping lands for major ports or when small craft get to close to whales in feeding or breeding grounds. Adjustments to ship speeds within areas known to have high whale traffic have been shown to lower the incidence of harm to the whale, and to the small boats involved.

- Whales are also at risk for entanglement in fishing gear such as crab or lobster pot lines. As food sources shift due to environmental pressures, whales end up coming closer to shore, increasing entanglements. Improvements are being explored for fishing gear that can benefit both the whale’s safety and the fisheries involved.

- Climate Change is also impacting both the location and availability of food sources which impacts everything from how well fed the whales which in turn impacts their birth and death rates. Actions taken to improve the climate will benefit all of us, the Humpbacks and other whales included.

There are many ways we can help protect and support whales, among them, speaking up for them and their (our) environment.

In the US, the Endangered Species Act which protects life on land, sea and in the air, is under threat. The Trump administration is proposing changes to the Endangered Species Act that would remove habitat protections for endangered species. “The proposed rule would pave the way for timber, oil, mining and other extractive industries, as well as the government and individuals, to destroy habitat where endangered species live, even if the damage to habitat harms those species. In so doing, the proposal rejects a 1995 ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the harm definition’s application to habitat destruction. As then-Justice O’Connor said in that ruling, “the landowner who drains a pond on his property, killing endangered fish in the process,” would violate the harm prohibition. Yet the new Trump proposal would call such harmful actions legal.” – Earth Justice 4/16/25

The deadline for public comments has be extended to September 22, 2025

Health Affairs has an update on the status of the challenge to the EPA

And after you commented, and shared the information and links with others, go outside, get on a boat – go see, hear, and smell a Humpback for yourself, it will be so worth the effort and might even change your life 🙂 It certainly changed mine.